The authors take a look at the past and future impact of the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission.

By: Anurag S. Rathore, PhD, Renu Jain, M. Kalaivani, Gunjan Narula, G. N. Singh

BioPharm International

Volume 11, Issue 27, pp. 35-40

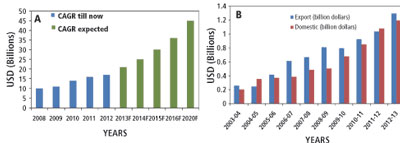

The past decade has seen considerable growth in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. India has emerged as a key supplier of high quality and affordable medicines not only to the developing world, but also to developed economies as well (Figure 1A) (1). This sector has recorded a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.5% over the past five years and is projected to reach $45 billion in 2020 (2). With the ongoing shift from small molecules to biologics, the Indian biopharmaceutical industry is also set to replicate the success received by the Indian pharmaceutical companies (Figure 1B) (1). The biopharmaceuticals market has witnessed the fastest growth in the 2013 financial year as compared to other biotech markets (e.g., Bio-Agri, Bio-Services, and Bio-Informatics).

The past decade has seen considerable growth in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. India has emerged as a key supplier of high quality and affordable medicines not only to the developing world, but also to developed economies as well (Figure 1A) (1). This sector has recorded a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.5% over the past five years and is projected to reach $45 billion in 2020 (2). With the ongoing shift from small molecules to biologics, the Indian biopharmaceutical industry is also set to replicate the success received by the Indian pharmaceutical companies (Figure 1B) (1). The biopharmaceuticals market has witnessed the fastest growth in the 2013 financial year as compared to other biotech markets (e.g., Bio-Agri, Bio-Services, and Bio-Informatics).

Growth in this sector has also burdened the public institutions that are responsible for ensuring that the marketed products are safe and efficacious. In India, the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI)-led Central Drugs Standards Control Organization (CDSCO) together with the State Authorities are primarily responsible for ensuring the quality of biotech therapeutics post-approval. The Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission (IPC), which creates and publishes the Indian Pharmacopoeia (IP), however, plays a key role. The IP, as per the Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940, prescribes the standards for drugs produced and/or marketed in India and, therefore, plays a significant role in the control and assurance of the quality of the pharmaceutical products (3). Unlike a lot of developing and developed countries, the standards stated in the IP are authoritative and legally enforceable by the Indian regulatory authorities (CDSCO and State Drug Regulators). In this 31st article in the “Elements of Biopharmaceutical Production” series, the authors report on the evolution and future of IPC. The focus of the article is on biotech therapeutics.

Figure 1: Growth of the Indian (A) pharmaceutical industry and (B) biopharmaceutical industry.

Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission

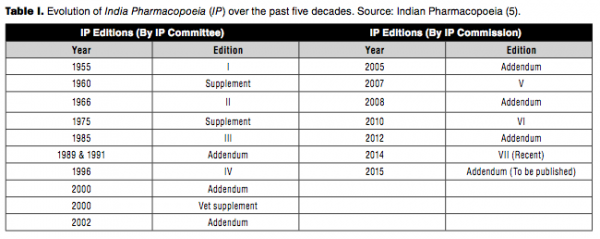

The IPC was constituted in 1948 with publication of IP defined as its primary function. The first IP was published in 1955 followed by a supplement in 1960. This pharmacopoeia contained both western and traditional Indian pharmaceutical products commonly used in India.

Thereafter, the IP has been published at frequent intervals. The frequency has increased with time due to the phenomenal growth in the number of pharmaceutical products over the past five decades as well as the diversity in their origin and content. Over time, the IP committee has deleted monographs for products that have become obsolete and added monographs based on the therapeutic merit and medical need (3).

The IPC was established in 2005 and the first addendum, which was published by IPC in 2005, included a large number of antiretroviral drugs and raw plants commonly used in making medicinal products not covered by any other pharmacopoeias, which attracted much global attention. Similarly, IP 2007 contained 271 new monographs with focus on those drugs and formulations that cover the National Healthcare Programs and the National List of Essential Medicines. The addendum in 2008 contained 72 new monographs (4). The commission had become fully operational as an autonomous body under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India in 2009 and released IP 2010 (5).

IP 2010 contained monographs on antiretroviral, anticancer, antituberculosis, and herbal drugs. It also included monographs of biologically derived products such as vaccines, immunosera for human use, blood products, and other biotech and veterinary (biological and non-biological) preparations. Addendum 2012 to the IP 2010 incorporated 52 new monographs (Table I) (3).

The primary objectives of IPC include the following:

The primary objectives of IPC include the following:

• Develop comprehensive monographs for drugs and upgrade them as needed

• Accord priority to monographs of drugs included in the National List of Essential Medicines

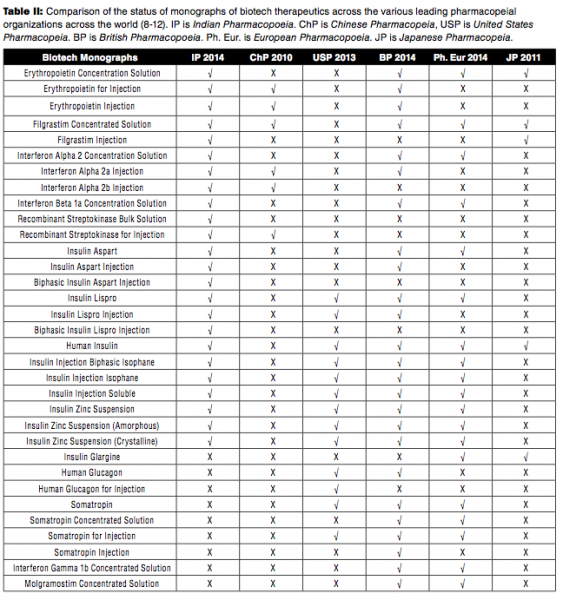

• Collaborate with other pharmacopoeia (e.g., United States Pharmacopeia[USP], British Pharmacopoeia [BP], Chinese Pharmacopeia [ChP], European Pharmacopoeia [Ph. Eur.], World Health Organization [WHO], and Japanese Pharmacopeia [JP]) to attempt harmonization with global standards

• Prepare, certify, and distribute IP Reference Substances

• Publish National Formulary of India

• Organize educational programs and research activities to generate awareness about the need for quality standards for drugs and related articles/materials (3).

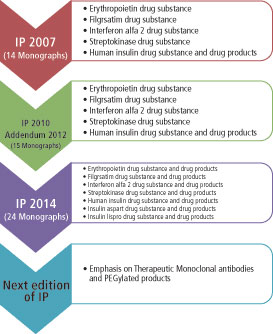

Figure 2: Evolution of Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission over the past decade.

Figure 2: Evolution of Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission over the past decade.

The scope of IPC has been extended to include products of biotechnological origin, indigenous herbs and herbal products, veterinary vaccines, and additional antiretroviral drugs and formulations, inclusive of commonly used fixed-dose combinations. IP 2014 had 577 new monographs and included monographs of API [134], formulations [161], excipients [18], new drug substances [43], antiviral [11] and anticancer [19], antibiotics [10], herbal [31], vaccine and immunosera for human use [5], insulin products [6], and biotechnology products [7]. IP 2014 also included 19 new radiopharmaceutical monographs and a general chapter on radiopharmaceutical preparations (4). Table II presents a comparison of monographs related to biotech therapeutics across the different international pharmacopoeial bodies. It can be seen that IP compares well with other leading global agencies. Figure 2 illustrates the evolution and key milestones of IPC since formation.

Challenges and Possible Solutions

While significant advancements have been made in the past decade by the IPC since its formation, the complexities of dealing with biotech therapeutics raise the bar further. The following are some of the key challenges IPC faces today with respect to successful creation and implementation of monographs of biotech therapeutic products.

• Limited experience with biotech processes and products. Limited experience with biotech processes and products is a challenge faced by many government organizations in India and across the world. Approval of the first recombinant DNA product, human insulin, occurred only in 1982. The experience is even more limited in India. The government, through agencies such as the Department of Biotechnology, actively funds events that allow for training and sharing of best practices and lessons learned. Such activities are essential for gradually building a strong foundation of in-house experts. For the interim, IPC will continue to rely on the scientific panels that presently provide scientific and technical supervision (6).

• Lack of in-house laboratory. While IPC has a laboratory for characterization of reference standards related to pharmaceutical products, it is in the process of creating a state-of-the-art laboratory for biotech products. At present, IPC relies on the National Institute of Biological (NIB) for this set of activities.

• Creation of reference standards for biotech therapeutics. Biotech products are complex in nature and, therefore, no two products are exactly the same (7). This really complicates the task of creating a reference standard for a biotech therapeutic. So far such reference standards are offered for only a handful of simpler biotech products, such as interleukin and insulin. IPC, together with NIB, is working on creating a robust strategy for creation, characterization, storage, and distribution of these standards to support the domestic biotech industry.

• Collaborations with other global pharmacopoeial agencies. The scope of activities at IPC along with the complexities associated with biotech therapeutics make it a necessary requirement that the various pharmacopeial agencies work together with a collaborative spirit. IPC and USP have been working closely together and organize an annual conference to share updates and ideas. Similar relationships need to be pursued with other global agencies such as National Institute of Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC), and European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM). As the IPC grows in its capabilities, such meaningful collaborations will be mutually beneficial.

Future Perspective

The primary responsibility of the IPC has been towards publishing the IP at a frequency that meets the requirement of the industry and the country. IP 2014 included several biotech monographs, and the next IP is likely to include many new biotech monographs as well in view of the increasing dominance of biotech therapeutics in the pharmaceutical marketplace. IPC is in the process of monograph verification stage for rituximab drug substance and drug product and teriparatide drug substance and drug product monographs. Many new general chapters pertaining to topics such as therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, host cell proteins and DNA, and viral safety are in the works for the next IP edition.

As mentioned previously, creating and implementing a process for producing, storing, and distributing reference standards for biotech therapeutic products is a key focus for IPC at present. To establish these standards, candidate materials can be sourced from multiple Indian manufacturers (with certificate of analysis) and calibrated against the originator product. Development of reference standards for biotech therapeutics can be done by collaborative studies involving the manufacturers and other government agencies such as the NIB. The WHO International Standard (WHO IS) could be considered at the highest level of hierarchy (primary standard) of reference standard. The reference standard should have the following key components:

Candidate materials sourced from the manufacturers must comply with the acceptance criteria provided in the IPC monograph. The certificate of analysis should be submitted and should include the critical quality attributes with respect to identity, content, and potency of the product. Stability of the material should be already established with its formulation/presentation defined by the manufacturer.

Assessment of suitability of the candidate material should be evaluated by IPC with respect to the content, formulation, and final presentation of reference standard material.

A multi-centric collaborative study should be planned to verify the IP reference standard. The detailed study testing protocol should include validated method to be followed for analytical testing, storage, and handling along with the procedures for reporting and submission of results.

Another major initiative for IPC is establishing a laboratory for verification of biological monographs and characterization of the reference standards for biological products. The laboratory will have state-of-the-art analytical instrumentation for testing/analysis of biotechnology therapeutics. The scope of the lab includes:

Development/verification of methods and limits for biological monographs

Development of IP reference standards for biotech therapeutics

The success of these two initiatives is crucial for IPC to make a meaningful contribution to the Indian biotech industry.

Summary

With biotechnology based therapeutics becoming increasingly important to India, organizations such as the IPC will need to evolve to effectively do their part in the process of bringing safe and efficacious therapeutic products to the market. This article presents an update on the challenges faced by the IPC and some of the significant initiatives that the organization is pursuing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the IPC’s Expert Committee on Biologicals and rDNA Products. These include Dr. S.S. Jadhav and Dr. Sunil Gairola (Serum Institute of India), Dr. Venkata Ramana (Reliance Life Sciences), Dr. Anil Kukreja (Roche Products Pvt. Ltd), Dr. Sriram Akundi (Biocon Foundation), Dr. Jaideep Moitra (Gennova Biopharmaceuticals), Dr. Rahul Kulkarni (Gennova Biopharmaceuticals), Dr. Himanshu Gadgil (Intas Biopharmaceuticals), Mrs. Kinnari Vyas and Dr. Susoban Das (Intas Biopharmaceuticals), Dr. Satyanarayana Subrahmanyam (Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Limited), Dr. Sanjeev Kumar (Zydus Cadilla) Dr. M. Kalaivani (IPC), Ms. Gunjan Narula (IPC), and Dr. Renu Jain (NIB). Prof. Anurag S. Rathore (IIT Delhi) is the Chairman of the Committee. Dr. G. N. Singh is presently the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) and is also the Scientific Director of IPC.

References

Association of Biotechnology Led Enterprises, Industry Insight, Biospectrum Asian Edition, Vol. 1 (June 2013).

PricewaterhouseCooper, India Pharma Inc.: Capitalizing on India’s growth potential (PWC, November 2010).

Indian Pharmacopoeia (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare), Govt. of India (2014).

R.M. Singh, “Role of Indian Pharmacopoeia for Quality Medicines in India,” Spinco Biotech Cutting Edge, 1 (6) (December 2013).

IPC,Indian Pharmacopoeia, 6th Edition (September 2010).

A. S. Rathore, BioPharm Inter. 24 (11) (November 2011).

A. S. Rathore and I. S. Krull, LC GC North America 28 (2010).

Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China, 2010, The state Pharmacopoeia Commission of P.R. China, China Medical Science Press, Beijing, China.

USP, USP 37 NF 32, United States Pharmacopoeia Commission (Unite Book Press Inc., Baltimore, MD 2014).

BP, British Pharmacopoeia, 2014 by The Stationary office on behalf of The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), (London SW1W9SZ 2013).

Ph. Eur., The Europoean Pharmacopoeia 8.0, Directorae for quality of medicines and healthcare of the Council of Europe (EDQM), Council of Europe, 67075 Strasbourg, Cedex, France (2013).

JP, The Japanese Pharmacopoeia, 16th Edition, Pharmaceutical and Medical Devices regulatory Science Society of Japan, Tokyo 150-002, Japan.

About the Authors

Anurag S. Rathore*, a professor, Department of Chemical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi, India

Renu Jain, scientist, National Institute of Biologicals, NOIDA, India

M. Kalaivani, scientific assistant, Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ghaziabad, India

Gunjan Narula, pharmacopoeial associate, Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ghaziabad, India

G. N Singh, Secretary-cum-Scientific Director, Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ghaziabad, India

*To whom all correspondence should be addressed.